By Nathan Beel

21 November 2024

(Pictures are from screenshots from the draft training standards)

If you are a member of the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia, or the Australian Counselling Association, you will probably have heard about the development of the national standards for counsellors and psychotherapists. These are a result of the Department of Health and Aged Care funding of $300k for Allen + Clarke consulting, to develop minimum standards for the counselling profession.

The draft version was developed from extensive written submissions and interviews, with stakeholders including counsellors and psychotherapists, the two peak bodies, consumers, and other interested stakeholders.

At this time, the draft version is ready for public consultation. It will close on Friday 13 December 2024.

My analysis

In my view, the document is pretty sound. Given the extensive consultation that formed the background for the draft standards, informed mostly by counsellors and psychotherapists and various working groups in the profession, it is unsurprising that the document is not too different to standards and practices in both the Australian Counselling Association (ACA) and in the Psychotherapy and Counselling Federation of Australia (PACFA).

This said, as it is a draft, I wish to offer my recommendations, many of which are informed by colleagues who I have discussed the draft with.

Expectations without protections

The draft rightly highlights minimum expectations for counsellors and psychotherapists, to ensure that the public is both protected from harm and that the profession aligns with government regulatory practices. The background for the standards recognises the important role counsellors and psychotherapists have in supporting Australian mental health and wellbeing. It also attempts to address the inconsistency between the ACA and PACFA in terms of training standards, guidelines, and practice. The aims are to be supported. However, my first concern is that these standards may create an unequal playing field between those who are part of the profession and thus accountable to these standards, and those who practice as counsellors outside of the profession. Skipping to the final focus area 4.1.4 Removal from practice, it highlights that breaches of the standards may lead to a withdrawal of membership. This implies that these standards only apply to registered counsellors (and psychotherapists, but from now on, I’ll just say counsellors as inclusive of both groups), not unregistered counsellors. In other words, registered counsellors who play by the rules can be removed from practice, and unregistered counsellors do not have a mechanism in these standards to be censured for problematic practice.

In addition to the penalisation of only registered counsellors, it may also disincentivise untrained or even trained but unregistered counsellors from joining as members. Why train, why pay membership, why be compelled to pay for monthly supervision, why pay for annual CPD, and why risk your practice by being a member when you can be a counsellor for no cost or risk? It seems the people who play by the rules bear the costs, the expectations and the risks, while those who practice outside of associations don’t have the same risks or costs. And the public is none the wiser as to who are registered or not.

The standards need either apply to all people who identify as counsellors, members or not, or there needs to be special protected titles for those who are registered, such as Registered Counsellors, or Licenced Counsellors. This way, the public may be better able to discern who is registered with the profession of counselling compared with who is not.

Lower trained counsellors treated as equivalent to more thoroughly trained counsellors

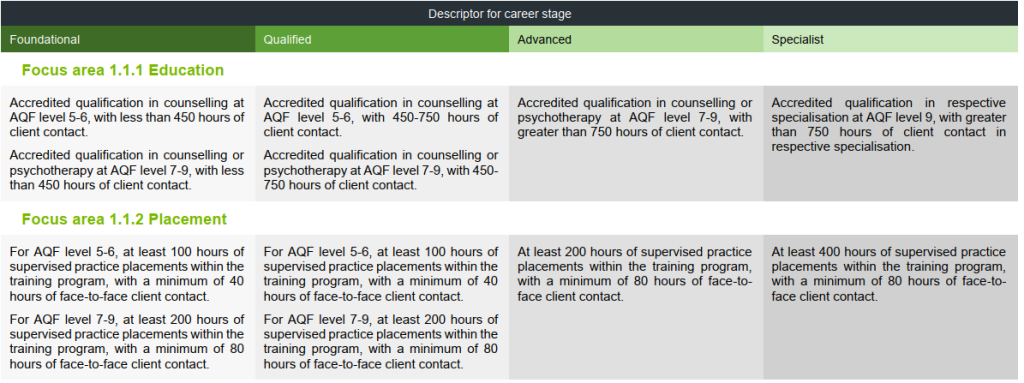

The first focus area that needs reconsideration is on education. The screen shows four columns, each moving from lower levels to higher levels.

The foundational and qualified levels capture diploma, bachelor and Masters level trained counsellors. I see two key issues with listing diploma and degree levels, essentially, as equivalent career stages. Firstly, diploma qualifications, which can be completed in just 12 months, are considered equivalent to degree qualifications that require two to four years of study in terms of level of the lower levels of standing. Secondly, diploma graduates are required to complete fewer placement hours (100) than degree graduates (200 hours). Are lesser qualified, lower trained, and less experienced diploma students really on the same level as degree plus students with more experience? Are the graduates trained as paraprofessionals on the same professional level as those who have had professional training and experience?

To address these concerns, introducing a pre-foundational stage and labeling diploma graduates as “Associate Registered Counsellors” could provide a solution. This distinction would recognise the value of paraprofessionals in counselling, supported by research showing they can achieve equivalent results to professionals. By differentiating associate counsellors from registered counsellors, similar to the nursing profession’s enrolled compared with registered nurses, the counselling profession can enhance credibility and transparency.

This proposed change would have several benefits. It would provide diploma graduates with additional credibility over unregistered counsellors, while clearly communicating their qualifications to the public. It would also address concerns about the reputation of the counselling profession appearing underqualified compared to similar professions that require a minimum of four years of university study. Furthermore, recognising the role of associate counsellors would support Australia’s counselling workforce needs, rather than potentially excluding effective practitioners.

Did COVID never happen?

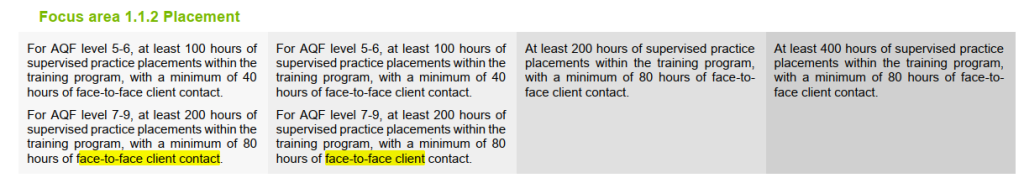

The draft standards have retained the obsession some have with misconceptions about the importance of face-to-face experience in the formation of counsellors. Placements do not mandate the type of issues, type of therapies, or whether they practice individual, couples, family, or group therapy formats. However, this set of draft standards targets and mandates face-to-face contact, even though the post COVID world has clearly now made other formats of practice delivered via technology, as recognised practice. Existing research on telehealth doesn’t support a face-to-face only-ist position for counsellors. While it finds that face-to-face differs from online and phone therapies, it generally finds equivalent outcomes, therapeutic relationship, and satisfaction for clients. It is not a second-rate practice, though the research indicates that therapists with less experience and knowledge about it, tend to hold incorrect assumptions and negative prejudices against it. Requiring face-to-face only for 80 hours disadvantages students who cannot travel to an agency to do face-to-face work (i.e. remote region students), or who may not intend to become face-to-face practitioners. I wrote an article where I explored relevant research and argued that this restriction is outdated and based on myths. See here. If they maintain the current position, can at least we treat teleconferenced sessions as face-to-face? While not all the body language can be seen, there’s still a lot of body language the counselling practicum student can hear and observe in the interactions. In fact, the proximity of this format of the faces to one another is more literally face-to-face than sitting in a room together a couple of metres apart.

Worried academics – be careful what you wish for?

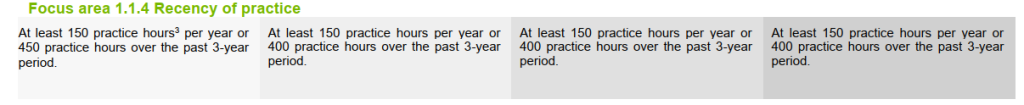

Another area that might raise eyebrows is the recency of practice. I think this is better labelled Currency of Practice as one could have met the requirements three years ago and not done any practice for the last two years, but still be considered having practiced recently according to this focus area criteria.

From a counselling academic perspective, keeping practice currency can be tricky. While some training institutions make space in the workload, others do not. This can put pressure on academics who are often time poor, working nights and weekends to keep up with their academic workloads, let alone adding practice on top of this.

As an academic, I am not advocating this be dropped even while I know that some of my academic colleagues might oppose this. The first reason is that I believe it is important for academics to maintain currency of practice. I know myself, how fast I become clinically rusty when away from practice for a month or two. I have been practicing for over 25 years and yet I can sense the impact of lengthy breaks. Another reason for keeping it as is, is that having this expectation as a minimum becomes grounds for peak body training standards to require institutions give counsellor educators release for practice, which in turn, should make allowance for in their workloads. Institutions that wish to retain accreditation will need to comply. Giving academics opportunities to maintain practice currency will enable them to provide higher quality current practice experience to speak from, rather than historical experience alone. Should currency of practice be removed, it will disincentivise academics from maintaining it. Being stale and out of touch with practice will in my view, reduce the richness of student experience and lead to academics being out of touch with the realities of contemporary client work. Students often have told me how differently enriching their experience is when taught by practitioners compared to academics without currency of practice. As a practice-based profession, I think we really we need to practice what we teach.

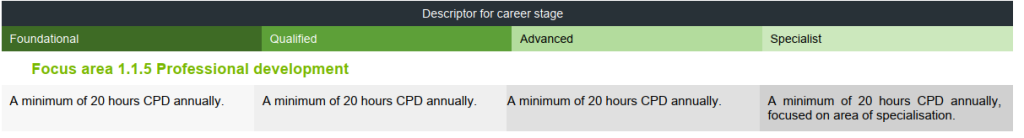

With the CPD criteria proposed, I don’t want to specialise

A colleague recently brought to my attention an issue with the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) requirements. Specifically, specialists who have completed Master’s level training in their area of specialisation are expected to dedicate 20 hours of CPD to that same area, year in, year out. For instance, a specialist drug and alcohol counsellor might be required to focus their professional development exclusively on drug and alcohol-related topics.

This raises concerns for me, as it seems overly restrictive. Clients with specialised concerns, such as addictions, often present with interconnected issues spanning multiple areas, like trauma. By limiting PD options to a single specialisation, practitioners may miss out on valuable training opportunities. While critics of my position might say that I could always do additional CPD in other areas relevant for practice, I would reply that I don’t want to be penalised with a burden of having to do over and above anytime I want to learn something outside of my specialty area. Sorry, this seems like a penalty for being recognised as a specialist. And additionally, it assumes there will always be opportunities for CPD in specialist areas every year. This may not be the case.

Personally, I’m inclined to maintain my advanced status rather than pursue specialist registration, solely to preserve flexibility in my professional development choices.

I recommend revising the CPD requirement to mandate only fewer hours in the specialization area. This adjustment would prevent discouraging professionals from becoming registered specialists, avoiding unnecessary limitations on their PD options, or increased demands.

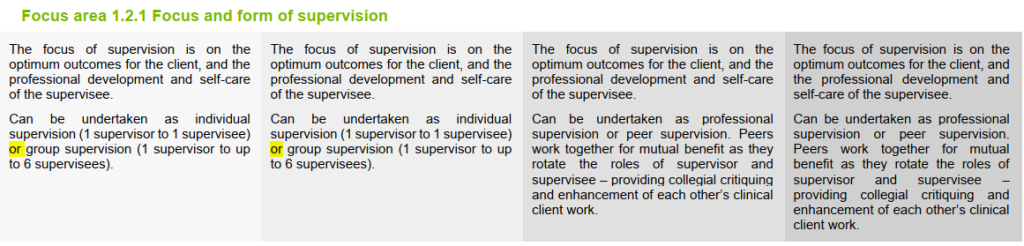

Avoidance or neglect for new counsellors – take your pick

In the standards, less experienced counsellors, including new graduates, don’t have to do individual supervision – at all. While this might save them money, as group supervision is often cheaper, I think this is a risk to the public. An inexperienced counsellor who may not have an opportunity in the group to talk about a difficult client issue that they need help for in the following session is problematic. Moreover, they may be less inclined to bring up more sensitive or embarrassing issues with a group compared to an individual supervisor who is there only for them in the supervision hour, with no witnesses. I have supervised many newly minted counsellors and I know how much individual support they need. I am horrified at this proposal and think it is highly risky.

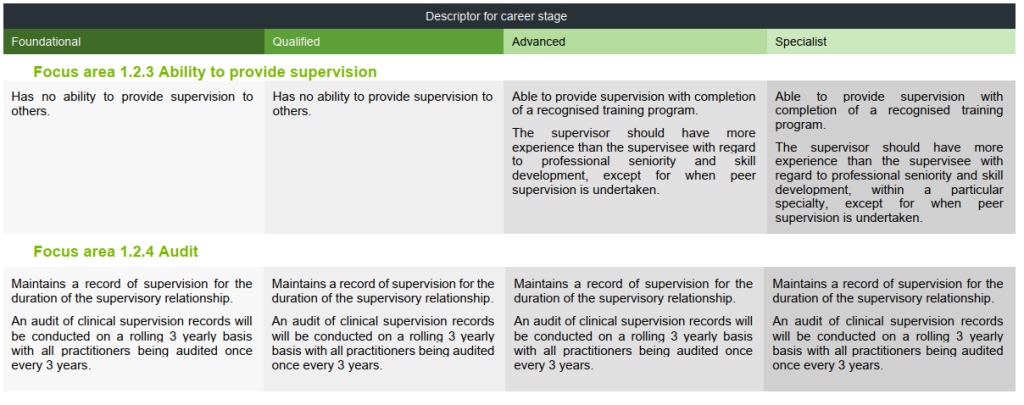

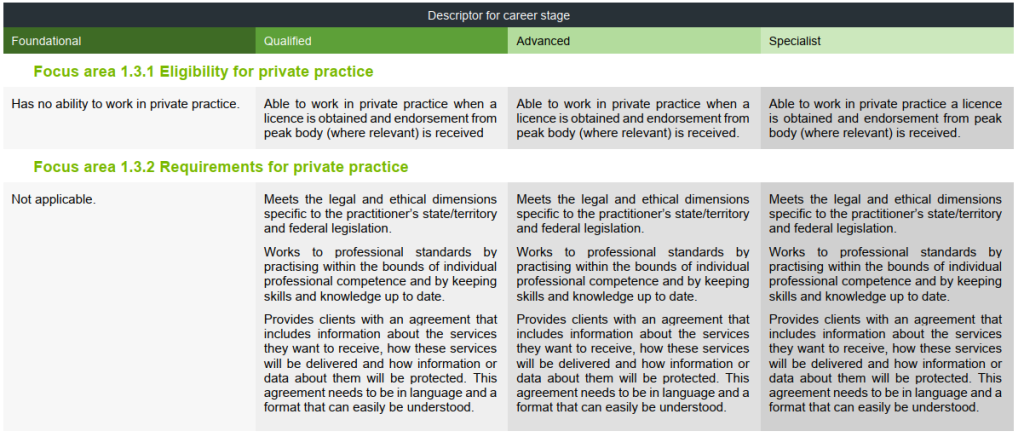

Cheers for supervisor eligibility and private practice restrictions

and

One pleasing update was that foundational and qualified counsellors are unable to provide supervision. This is welcomed to prevent the inexperienced guiding the inexperienced.

There’s also a useful update about eligibility for private practice, wherein there is a recognition that private practice has complexities and risks some with lower qualifications may be less likely to recognise or manage. While there will be some lower qualified and experienced private practitioners who do a great job, these standards address a risk that still continues to this day.

One of the challenges and reasons many counsellors have been attracted to private practice is because the employment market has discriminated against counsellors, making counsellors needing to explore alternative opportunities to practice. I really hope the national standards help to enhance employer respect and willingness to hire counsellors. I appreciate the ACA and PACFA’s efforts to educate industry about what counsellors can do, and both to create Scope of Practice documents as part of this education.

Researching confusion

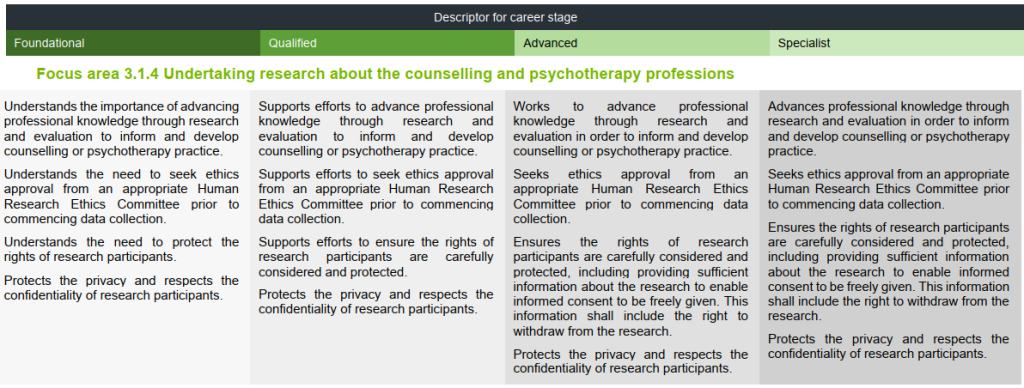

The focus area on research I found somewhat problematic. First, why is the label about undertaking research about the counselling and psychotherapy professions. Why do we need research on the profession as a minimum standard?? Can’t counsellors research other areas related to counselling too?

Also, the section appears to focus on the conducting of research. Firstly, diploma and bachelor students may have between nil and very little research training on average.

The second point I want to make is that rather than focusing on conducting research, shouldn’t require counsellors to be research literate? Very few practitioners will actually conduct and produce research, but all should be able to consume and understand research that might inform their practice. I agree with the importance of what is proposed. I just wonder about its relevance for the lower levels of trained counsellors who are unlikely to have had the relevant training to begin with, and unlikely to gain ethics approval if not having had sufficient research training.

Expert over or collaborate with

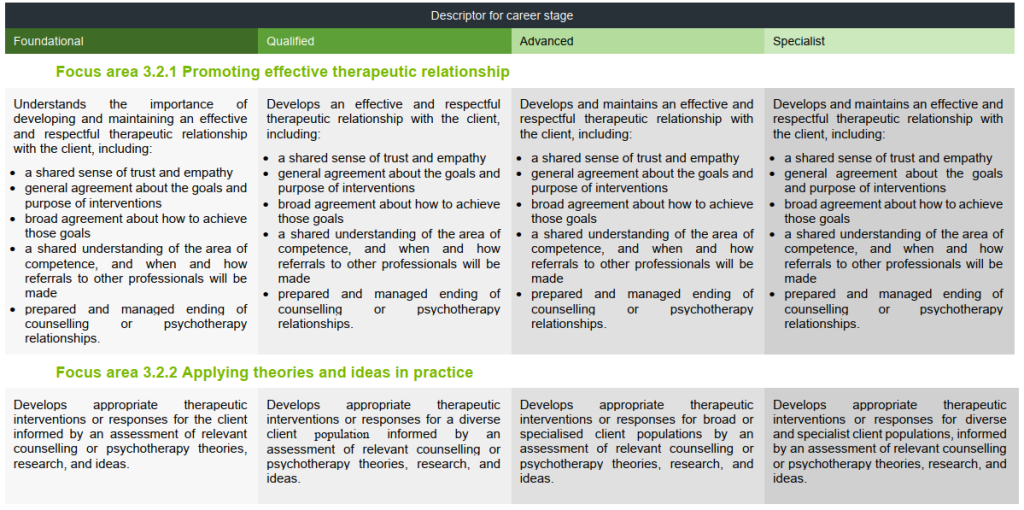

This is my last two areas for critique. 3.2.1 addresses promoting effective therapeutic relationship. First, we don’t promote the effective relationship, as stated in the focus area title. We don’t’ tell clients, “hey, I think you should really enter into a therapy relationship. It’s a really good thing”. No. Counsellors develop or facilitate it. Overall, though, I think this is an important focus area given the counselling profession, in my view, prizes the relationship.

The focus area 3.2.2 on applying theories and ideas in practice. It’s basically saying we should be theoretically informed. No disagreement here. However, the way it is written seems to exclude the client’s voice. In counselling, we do not impose theories or our ideas based on theories onto clients, but there is an interaction between client and counsellor knowledge. It isn’t a top-down expert over process about an interactional process of decision making.

Categorical confusion?

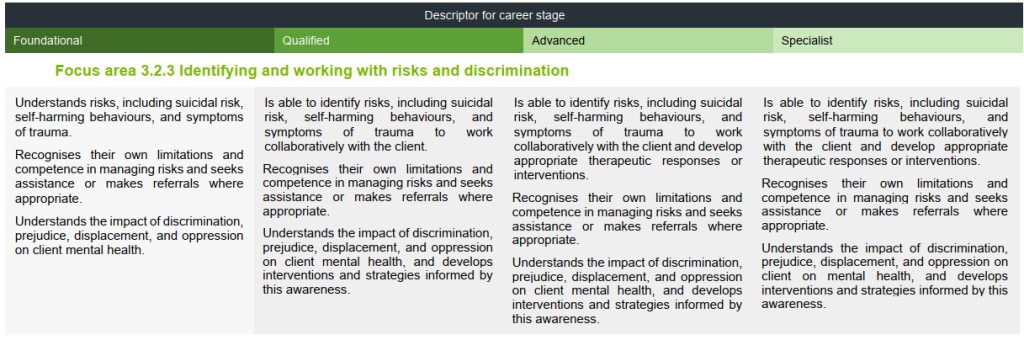

I’m not sure I understand how identifying and working with risks is directly and intrinsically related to discrimination. Focus area 2.1.3 is on respecting diversity, so I would have thought this area is of relevance to the discrimination category. However, I’m happy to be corrected. I just don’t see it at this time.

Conclusion

I’ve listed some of my concerns, not to diminish the perception of the quality of the standards overall, but to highlight some areas that might be worthwhile to reconsider. If you agree with some or all of my points, please use them in your feedback in the survey and share the link to this page with your fellow counsellors.